A guest post from the ICS cyber security blog:

Guest Post II: A post that has no cybersecurity relevance. Or maybe it does.

20 February 2021 – icscybersec

One of the most serious operational security events in recent times, the January 8th rupture of the European electricity system into two parts, has prompted another post by my colleague GéPé:

In my previous post, I deduced that two unrelated incidents were in fact related.

As a model for that, today I present a case that has no cyber security relevance. Or maybe it does?

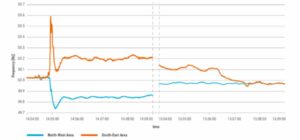

On January 8, a rare event occurred. At 14:05 central European time, the single European electricity system was split into two parts, the north-western part marked in blue and the south-eastern part marked in yellow. Source from

After the split, the north-western part of the grid started to lose frequency due to a higher consumption than electricity generation of about 6.3 GW. At the same time, frequency in the South-Eastern part of the grid started to increase due to higher generation than consumption. In the North-West part of the grid, around 1.7 GW of large consumers in France and Italy were disconnected to stop the frequency decrease. At the same time, generating capacity in the south-eastern part of the network was disconnected to take account of the generation surplus. The European electricity system was split into two parts for almost 1 hour, with frequency variations and movements as shown in the figure below, until the two parts were interconnected and the unified system was restored.

The analysis so far – not yet fully detailed, but correct in its main lines – indicates that the so-called overcurrent protection at the Ernestinovo substation in Croatia, which connects the two 400 kV busbars, was tripped by the so-called overcurrent protection. It is not known at this stage whether there was an increase in the current that justified the operation of the overcurrent protection or whether the protection actually tripped the busbar circuit breaker without any reason.

The question obviously arises: what is the cyber security relevance of all this?!

Let’s look at what happened! Somewhere in Europe, the tripping of a single (!) circuit breaker split the unified European electricity system – and made it temporarily unstable – in such a way that a single, stable operation was restored only after 1 hour.

With this in mind, let us consider the following. What if a highly skilled, resource-rich (say APT) attacker could identify this one – or a few more – key circuit breakers and exploit SCADA and/or RTU and/or defence vulnerabilities to shut down the breaker(s).

Let’s not think that this is impossible! With not too much research (even passive OSINT), the topology of the European power system can be understood. With a little expertise, a computer model of the network can be built, on which the effects of the various connections can then be simulated. For a state-backed attacker, an APT, this should not be a problem. Recall the 2016 attack on e.g. the Pivnichna (Ukraine) transmission substation, which demonstrated in practice the attacker’s high level of knowledge of electricity technology!

In Europe, the continental outage of 4 November 2006 was the most important demonstration that, unfortunately, there can be system elements whose shutdown can cause avalanche-like outages – with widespread supply disruptions and consequent damage. In northern Germany, a 400 kV transmission line across a river was switched off as a precautionary measure to ensure the safe passage of an oversized ship. The operation was carefully planned and the expected load distribution was modelled. However, for some reason the switch-off was brought forward. At this point, the load conditions were different from those modelled. After a series of line outages due to overloads triggered by the transmission line shutdown, the unified European electricity system was split into three parts in 18 seconds. In one of the “islands”, the blackout could only be prevented by mass consumer restrictions, causing huge damage. In this case, too, there was a critical network element whose shutdown was capable of triggering a system blackout.

Note that both the continental system blackouts in January this year and in November 2006 were caused by the tripping of a single (!) network element. Let there be no doubt that an attacker who can eject a single system element would not be able to exacerbate the effects by ejecting additional, well-chosen system elements, up to and including blackout!

The US recognised years ago the danger of a continent-wide blackout by dropping a few critical network elements. According to a 2014 study, there are 9 of the 55,000 substations in the US (four in the East, three in the West and two in Texas) whose pronunciation on a hot day could trigger a continental blackout.

The incident in January this year showed that the European electricity system can be in a critical situation where the failure of one or a few system components – in the worst case, an offensive knockout – can cause widespread disruption, or in extreme cases a blackout.

The chances of this happening are increased if we ourselves carelessly make sensitive data on our network available to an attacker, without regard to the risk of data being obtained by OSINT.

But above all, do not underestimate the attacker’s ability! As Sun-Ce wrote: “Do not underestimate any enemy, for that may well be exactly what he expects.”

***

The original guest post was published on the ICS cyber security blog.

Translated by DeepL.